Aerin

"Books are the plane, and the train, and the road. They are the destination, and the journey. They are home."

- Anna Quindlen

Short story review: "The Next In Line", Ray Bradbury

This is the first in a series of single-serving short story reviews. Though I am not certain about my future at GoodReads, or my satisfaction with BookLikes as an alternative, the blog format over here makes it ideal for reviewing short fiction individually - something that had always been awkward on GR.

It's October, so I'll start with something creepy.

In 1945, Ray Bradbury visited Guanajuato, Mexico, and "The Next in Line" is the disturbing result. It's one of my favorite scary stories, not least because the truth behind it is so unnerving on its own. Where many horror writers take something mundane and make it spooky, here Bradbury takes something spooky and makes it terrifying.

It all started because of a grave tax imposed in Guanajuato in 1865. Relatives of the dead were required to pay annually to keep their dearly departed underground; fail to pay up, and your loved one's corpse would be dug up to make room for someone else in the crowded cemeteries.

When they began to exhume bodies, however, the authorities discovered that many of them had naturally mummified in Guanajuato's arid soil. And what do you do with a bunch of disinterred mummies whose deadbeat descendents won't pay the grave tax? Stand 'em up in a line, of course, and charge tourists a couple of pesos to gawk.

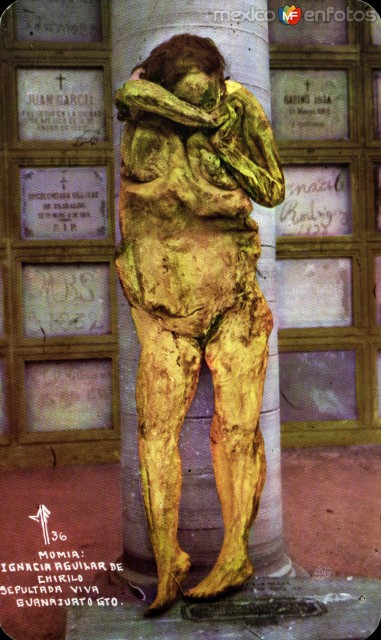

This is what disturbed Bradbury so much when he and a friend visited the Museo de las Momias in 1945. And it's easy to see why:

Because holy shit, that's why.

And as if these tranquil corpses weren't freaky enough, there's Ignacia Aguilar. Believed to have died from a heart condition, it was discovered upon digging her up that in fact she'd died of being buried alive - which was a thing that happened disturbingly often back in the day. Bradbury's characters tell her story:

"Here is an interesting one," said the proprietor.

They saw a woman with arms flung to her head, mouth wide, teeth intact, whose hair was wildly flourished, long and shimmery on her head. Her eyes were small pale white-blue eggs in her skull.

"Sometimes, this happens. This woman, she is a cataleptic. One day she falls down upon the earth, but is really not dead, for, deep in her, the little drum of her heart beats and beats, so dim one cannot hear. So she was buried in the graveyard in a fine inexpensive box. . . ."

"Didn't you know she was cataleptic?"

"Her sisters knew. But this time they thought her at last dead. And funerals are hasty things in this warm town."

"She was buried a few hours after her 'death?'"

"Si, the same. All of this, as you see her here, we would never have known, if a year later her sisters, having other things to buy, had not refused the rent on her burial. So we dug very quietly down and loosed the box and took it up and opened the top of her box and laid it aside and looked in upon her--"

Marie stared.

This woman had wakened under the earth. She had torn, shrieked, clubbed at the box-lid with fists, died of suffocation, in this attitude, hands flung over her gaping face, horror-eyed, hair wild.

"Be pleased, señor, to find that difference between her hands and these other ones,"said the caretaker. "Their peaceful fingers at their hips, quiet as little roses. Hers? Ah, hers! are jumped up, very wildly, as if to pound the lid free!"

"Couldn't rigor mortis do that?"

"Believe me, señor, rigor mortis pounds upon no lids. Rigor mortis screams not like this, nor twists nor wrestles to rip free nails, señor, or prise boards loose hunting for air, señor. All these others are open of mouth, si, because they were not injected with the fluids of embalming, but theirs is a simple screaming of muscles, señor. This señorita, here, hers is the muerte horrible."

And here's Ignacia, discovered face-down in her coffin, arms up by her scratched and bloodied face, as though she had attempted to push up the coffin lid with her back:

Clearly, this tale did not need much embellishment to freak a reader out. But that's Bradbury's genius, because "The Next in Line" isn't really about a bunch of creepy-ass mummies. Or in any case, not just about a bunch of creepy-ass mummies. It's the living in this story that are infinitely more frightening.

Note: Spoilers follow.

"The Next in Line" opens with a middle-aged American couple, Joseph and Marie, on vacation in a small Mexican town. Joseph is eager to check out the famed mummies on display in the cemetery catacombs, but Marie is skittish and filled with a formless dread. Just that morning, they had witnessed a funeral procession for an infant, and Marie is fixated on morbid thoughts:

He said, "Some little girl or boy gone to a happier place."

"Where are they taking-- her?"

She did not think it unusual, her choice of the feminine pronoun. Already she had identified herself with that tiny fragment parceled like an unripe variety of fruit. Now, in pressing darkness, a stone in a peach, silent and terrified, the touch of the father against the coffin material outside gentle and noiseless and firm inside.

That is not the right state of mind for descending into the catacombs to rub elbows with the unquiet dead. And indeed, when Joe drags her down there, she doesn't take it too well.

Marie counted in the center of the long corridor, the standing dead on all sides of her.

They were screaming.

They looked as if they had leaped, snapped upright in their graves, clutched hands over their shriveled bosoms and screamed, jaws wide, tongues out, nostrils flared.

And been frozen that way.

All of them had open mouths. Theirs was a perpetual screaming. They were dead and they knew it. In every raw fiber and evaporated organ they knew it.

She stood listening to them scream.

Meanwhile, Joe is giving the mummies silly nicknames and telling them to "say ahh!" Such a comedian!

So it's no surprise that Joe and Marie's marriage is in trouble. One sentence early in the story cuts to the heart of it: She lay back and he looked at her as one examines a poor sculpture; all criticism, all quiet and easy and uncaring.

But as the story continues, it becomes increasingly clear that Joe is not just inconsiderate, but actively and derangedly cruel. Mocking Marie's obvious distress over the mummies, he insists on buying a candy skull left over from the Day of the Dead. He relishes eating it in front of her, making sure she notices that it is emblazoned with her own name.

Then, when she insists that they leave the town right away, the car mysteriously breaks down, requiring days of repair. Trapped in this town with its buried, screaming secrets and this mocking stranger in her bed, madness creeps in on Marie.

What, after all, is the difference between a living person and those howling mummies? Skip a few too many heartbeats, miss a few too many breaths, and we'll all end up just lifeless skin stretched over bones. Marie becomes obsessed with her own heartbeat, terrified that it will abruptly stop. Or that one tiny malfunction in a single cell will metastasize catastrophically. But it isn't her own body she needs to fear. It's the other body in the room, whom she begs - as her psychosis deepens - not to bury her in the catacombs. She pleads with Joe, screaming - "Promise me!"

But he laughs at her, and he will not promise.

It's never clear what brought Joe and Marie to this place - why he despises and she cowers in fear. Was he planning to murder her all along? Is that why he's dragged her down to Mexico? Or is it the trip itself, this endless traipse through foreign terrain, that drives them to destruction? Marie says:

"Mexico's a strange land. All the jungles and deserts and lonely stretches, and here and there a little town, like this, with a few lights burning you could put out with a snap of your fingers."

And it is, in the end, Marie's light that is snuffed. Maybe her own madness did her in after all, or maybe not. All we see in the end is Joseph driving away alone, humming absent-mindedly with his little sheepish smile.

You can almost hear the corpses screaming.

5

5

6

6